Happy first Sunday, folks! Did you take communion? If not, no worries, I ain't your pastor and I ain't God. So I ain't judging! For a long time, I've had a mild fascination with the Appalachia region. No, I'm serious. It almost mirrors my life to a "T" as a child in the rural South. The two regions have more in common than most like to admit. 'Course there the glaringly obvious similarities like politics, right? Blue dots in expansive and vast red areas. The racism, which racism in the country looks way different than it does in any American city. Then there's the poverty. Poverty so bad that if there ain't no bus routes, your closest food source is 30 minutes by car (and that s if you have access to a car), and sometimes it's only a Dollar General with almost expired canned foods. The kind of destitution you can only believe if you'd seen it up close. Drug use is similar, but there are some differences. The Deep South and more southern regions of Appalachia favor alcohol and shine over other pills and injectables, though that's not to say those drugs aren't prevalent. But there's goodness too! The best part, if you ask me, about these regions. The food, poor folks can stretch some food, chile, while making it delicious. The heart, soul, and pride of being undeniably country can be found in the Deep South and Appalachia. Let's get into it a bit more.

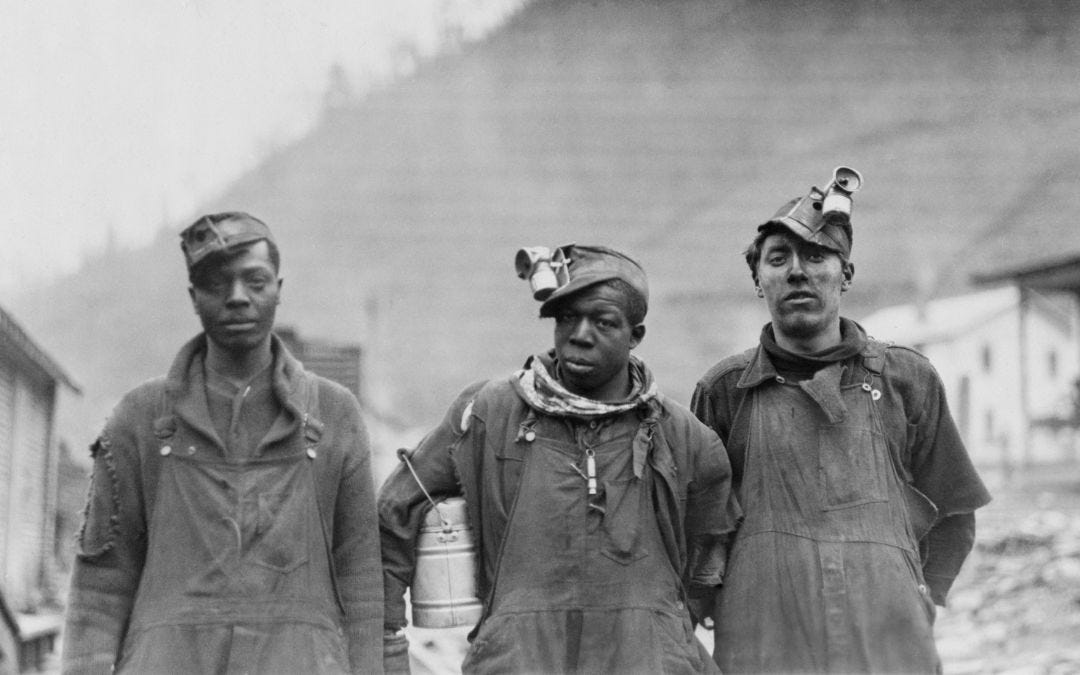

Both places got built on somebody else making money off folks' backs. In Appalachia, it was coal companies coming in and taking what they wanted from the mountains. In the Deep South, it was cotton and the whole plantation mess. Different industries, same playbook, take what's valuable, leave the people to deal with what's left.

The coal camps up in the mountains weren't all that different from sharecropping down South. Company owns your house, company owns the store where you buy your groceries, company makes sure you never quite get ahead. Whether you're underground digging coal or out in the fields picking cotton, you're working your tail off to make other people rich.

But here's what's beautiful about both places, they found ways to turn that struggle into something powerful. Music became the way to tell those stories. The ballads that came down from the mountains and the blues that rose up from the delta might sound different, but they're doing the same job. They're saying "this is what it's like to be us, and we ain't ashamed of it."

Go to a little Baptist church in rural Alabama or a Pentecostal service in a West Virginia holler, and you'll see the same thing, people who take their faith seriously and ain't afraid to show it. It's not the buttoned, up religion you might find in a city church. It's loud, it's emotional, it's real.

That faith shows up in how people treat each other too. When somebody's in trouble, folks step up. House burns down? Neighbors show up with food and whatever cash they can spare. Someone gets sick? The church ladies organize a meal train. It ain't formal charity, it's just what you do.

But that closeness can be a double, edged sword. The same community that'll take care of you when you're down might not be too happy if you start wanting to do things differently. If you're gay, or if you want to move to the city, or if you start questioning things that everybody else takes for granted, you might find yourself caught between loving your people and needing to be yourself.

Both places have this weird relationship with government. On one hand, federal programs brought electricity to mountain communities and roads to places that barely had them. Social Security and Medicare matter a lot when you're talking about areas where people don't have a lot of money saved up for retirement or healthcare.

But then you've got the other side, the feeling that people in Washington don't understand what life is like here, and they're always trying to tell you how to live. Environmental regulations that might shut down the last coal mine in the county. Federal agents coming in to enforce civil rights laws that challenge the way things have always been done.

Politicians love to come through during election season and talk about "real America" and "forgotten communities," but most of the time they're just using these places as props. They'll promise to bring back coal jobs or save the family farm, but when push comes to shove, not much changes.

The opioid crisis hit both regions hard, and it showed how easy it is for outside companies to come in and wreck communities that are already struggling. Same old story, take what you can, leave the damage behind.

Turn on the TV or watch a movie, and you'll probably see the same tired images of both places. Appalachians are all supposed to be toothless hillbillies who marry their cousins, and the Deep South is all Confederate flags and racial tension. It's lazy and it's wrong, but it's what gets put out there.

The reality is way more interesting. These places have given America some of its best music, from bluegrass to blues to rock and roll. Writers are telling stories that matter to people everywhere. You've got cities like Nashville and Atlanta right alongside rural communities, and plenty of people working to figure out how to honor where they come from while building something new.

The music that comes out of these places ain't stuck in the past either. Artists like Tyler Childers and Rhiannon Giddens are taking old traditions and making them speak to what's happening right now. They're not trying to be something they're not, but they're not trapped by other people's expectations either.

Now let me tell you something about folks in both these regions, they can make a dollar stretch further than anybody else in America. When you don't have much, you get real creative real quick. It ain't just about being cheap, it's about being smart with what you got.

In both Appalachia and the Deep South, people learned to make meals from whatever's in the pantry or growing in the garden. Hand- me-downs get passed down through generations, and when something tears, you mend it instead of throwing it away. Neighbors trade services all the time, I'll fix your roof if you help me with my garden. You grow your own food, can and preserve everything you can, and you learn to fix just about anything yourself instead of paying someone else to do it.

I remember my Grampie would reach out to this man named Cigar who could work on cars, trucks, etc. And instead of taking his Jeep to the dealership, Grampie would call up Cigar, and I suppose he was good at what he did — when he actually showed up. If something needed to be fixed on one of his vehicles, Grampie would call Cigar buku times. Half the time he showed up. Anyway, when he did come through, he'd save my Grampie hundreds of dollars, so it was worth the hassle, chile. That's how it works, you find people in your community who have skills you need, even if they ain't the most reliable, and you figure out ways to make it work.

Entertainment happens at home too. You make your own music, tell stories on the porch, play cards, have big family gatherings where everybody brings something to share. You don't need to spend money to have a good time when you've got people who care about you and the creativity to make something from nothing.

Both regions understand that being resourceful ain't just about surviving, it's about taking pride in being able to make do. There's dignity in being able to solve your own problems and help your neighbors solve theirs.

Both regions are dealing with the same basic problem, how do you keep a community going when the old ways of making a living don't work anymore? Coal mines shut down, factories move overseas, family farms get bought up by big corporations. Young people move away because there aren't jobs, and pretty soon you're looking at empty downtowns and schools that don't have enough kids.

Some places are figuring it out. Tourism can work if you've got something people want to see. Tech companies sometimes set up shop in smaller cities where the cost of living is lower. Local food scenes are taking off, with restaurants and breweries that celebrate what grows around here.

Climate change is making things more complicated too. Mountain communities are dealing with more flooding, coastal areas are seeing stronger hurricanes, and everybody's trying to figure out how to adapt. It's not just about the weather, it's about economics too, as old industries become less viable and new ones emerge.

But there's also reason for hope. Young people are finding ways to stay connected to their roots while building new kinds of businesses. Artists and writers are telling stories that show these places are more than just stereotypes. Food culture is having a moment, with chefs and farmers working to preserve old ways while appealing to new tastes.

The thing about Appalachia and the Deep South is that they've been counted out before, and they've kept going anyway. Both places have this stubborn streak that comes from having to make do with what you've got and not expecting anybody else to save you.

Maybe that's what the rest of the country could learn from these places, that community matters, that tradition has value, that you can be proud of where you come from even when it's complicated. That dignity don't depend on having money or status, and that some of the most important things in life can't be bought or sold.

The conversation between these regions is still happening, in songs and stories and everyday interactions between people who recognize something familiar in each other. It's about what it means to belong somewhere, and how that belonging shapes who you become.

When Loretta Lynn sang about being a coal miner's daughter, she wasn't just talking about coal miners' daughters. She was singing for anybody who's ever felt like the world didn't quite understand their story but knew it mattered anyway. That voice is still out there, in mountain hollers and delta towns, wherever people are working to build meaningful lives in places that others have written off.

The parallels run deeper than geography or politics, they're about resilience, about community, about the ongoing challenge of being authentically American while maintaining what makes these places special. And they're about recognizing that sometimes the most important stories come from the places that everybody else overlooks. Yall know what I'm talking about. I’ll see yall next time!