Grace by the water

Examining the evolution and current relevance of the Black church, considering its historical significance and the challenges it faces in today’s context.

When I was younger, like most of my peers, I went to church. Mostly, it was against my will because, well, church was boring and lasted many, many hours—at least to a child. My maternal grandmother came from a long line of believers, folks who went to church and praised God every Sunday just as their parents had done before them. Because of this legacy, I found myself sitting in a pew every Sunday. It was expected of me, just as it was expected of the generations before. Church started at 10 a.m., and we would be out of the house at least 30 minutes before that.

As I got older, my grandmother didn't force me to stay the entire service, allowing me to leave right after the public offering. This gave me about 10-15 minutes of freedom before the entire congregation was dismissed. It wasn’t much, but it was enough for me because, truth be told, I didn’t want to be there anyway. I was expected to attend, but no one expected me to enjoy it. Yet, like most kids, I made the best out of an unpleasant situation.

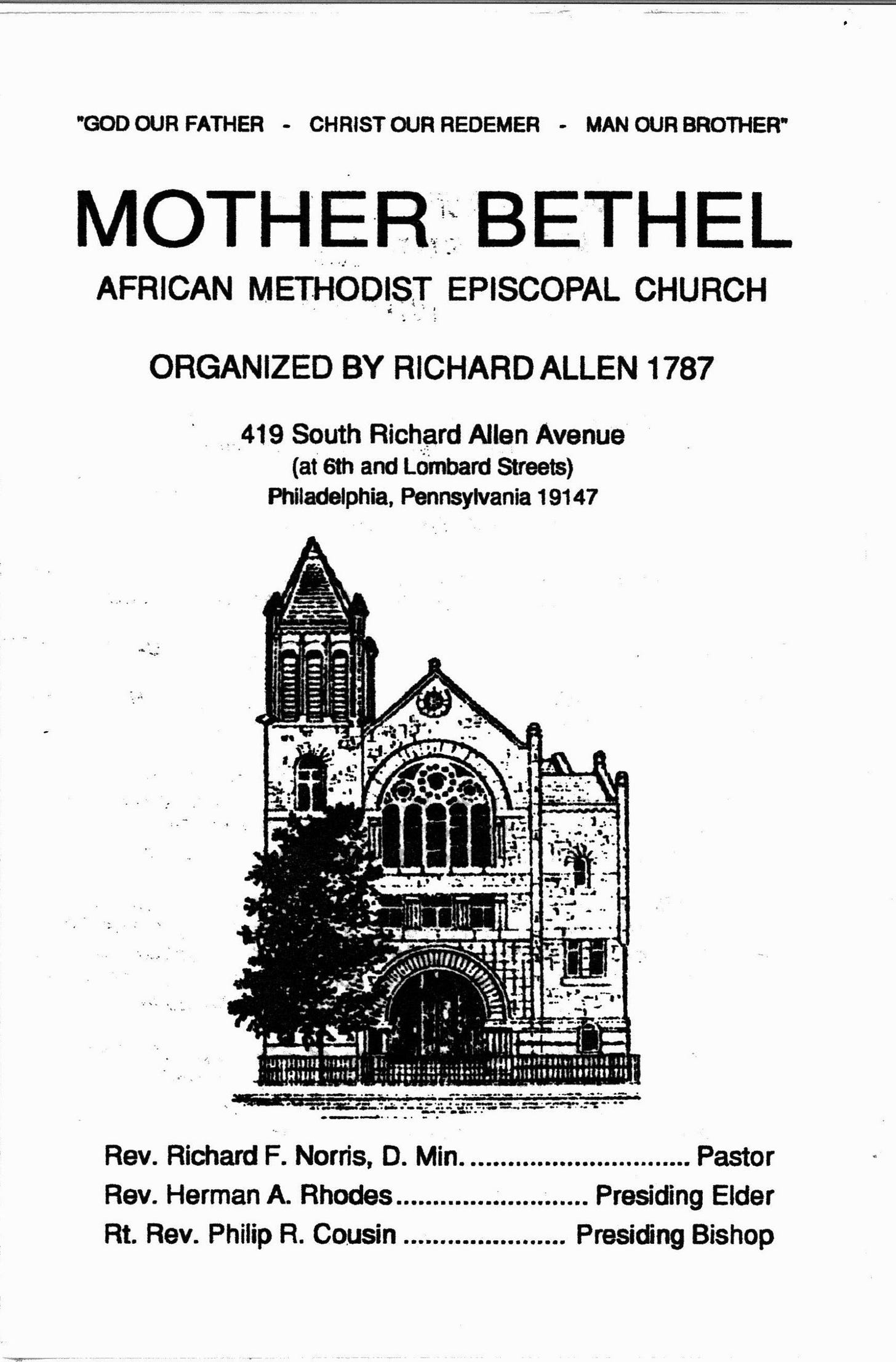

As time passed, I found myself getting more involved in church activities. I attended conferences, took on a role in the YPD (Young People's Division), and even became an usher. I was all in! Many of my mother’s family members were involved in church in some capacity. In fact, if you've ever seen The Color Purple—the movie, not the monstrosity of a musical Oprah produced—you'll have a good sense of the kind of church I grew up in. The one depicted in the movie, where Shug Avery’s father is the pastor, closely resembles my childhood church. When I was about 12, that building was replaced with a more modern structure, which still stands today.

Church is something deeply ingrained in me, and I have not only my grandmother to thank for that but also the village that raised me. It was more than a place of worship; it was a community hub where the hungry were fed, the sick were cared for, and everyone came together. Church was the center of my life for a long time. During the summers, I’d attend Vacation Bible School or various retreats at different churches, each unique in name and denomination, all Black. But if you were to ask my cousins, they’d probably say my involvement was a "light load" compared to theirs. After all, I grew up with four cousins who were "PKs"—preacher's kids—and one of them has even gone on to become a pastor himself.

Some people boast about their family’s political power or wealth, but I take pride in my cousin being a pastor. Of course, I brag about all my family’s accomplishments because, well, I’m proud of them! Being in the church as a child has undoubtedly shaped the woman I am today. However, after much introspection, I wouldn’t describe myself as overtly or if at all religious at this point in my life, but I am probably the most spiritual person one would come across. And, suge, religion and spirituality are not the same—though that’s a conversation for another day.

Growing up in a rural area, surrounded by sugar cane fields, dilapidated houses, a bayou, and the closets Walmart being 15 minutes away, although, my Grampie could probably make it in 5, church was more than just a respite from the boredom of “small town life” it was a pillar of the community. This was especially true in the south, where Black churches have long held a unique and vital role, particularly during the dark days of Jim Crow.

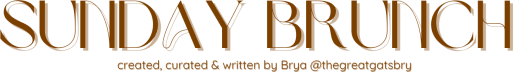

During this era of legally enforced racial segregation and disenfranchisement, the Black church was not only a place of worship but also a sanctuary from the pervasive injustices of the time. It served as a meeting ground for those plotting resistance, a space where strategies for survival and progress could be discussed safely, away from the prying eyes of those who sought to oppress. The church was the heart of the Civil Rights Movement, providing both spiritual sustenance and practical support.

One of the most powerful examples of this can be seen in the life and legacy of Senator John Lewis. Before he became a towering figure in American politics, John Lewis was a young preacher, deeply influenced by the teachings and strength of his local Black church. It was there that he honed his oratory skills and developed a profound sense of justice and morality that would later propel him into the heart of the Civil Rights Movement. The church nurtured his spirit and provided the moral foundation upon which he would stand as he led marches, faced down violent opposition, and crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday in Selma.

His unwavering faith, deeply rooted in the Black church, fueled his lifelong commitment to fighting for equality and justice. The hymns sung within these churches carried messages of hope and determination, fueling the spirits of those who marched, protested, and fought for the rights we often take for granted today. The Black church, with its roots in resistance and resilience, was, and still is, a beacon of hope in the face of adversity, proving time and again that faith and community can overcome even the most entrenched systems of oppression.

Being Black in America, not just in the South, means that church is in our blood. Despite religion and church being used against them, my ancestors took the religion of their oppressors and used it to inspire hope, optimism, and even Hoodoo.

Over the decades, the Black church has been a safe haven for Black people in America—a place to feel safe, validated, and comforted. During the 1800s, when slavery was the backbone of wealth for the lazy and pompous who declared themselves powerful, Christianity was imposed as the default religion. Something that still boggles my mind is how plantation masters used the threat of burning in Hell to frighten slaves into submission.

Slaves were prohibited from learning to read, keeping them in ignorance. Religion and spirituality can coexist and should, but remember those pompous, lazy people I mentioned? Of course, they would use something as sacred as religion to push a narrative that justified free labor, genocide, or any other form of oppression that served their interests at the time.

Activists like Malcolm X and the entire Black Panther Party believed that modern Christianity, as we know it today, was and continues to be a method of control. But because of the comfort that church provides—the sense of community—can you fault someone who refuses to believe otherwise? Would it be fair to ask someone to abandon what makes them feel whole, something they’ve believed in for years, sometimes since birth?

For me, church is where the heart is, a place where the only judgment that mattered was from God. Some church folks do manage to give church a bad name, those that are judgmental, unwelcoming and catty, but if you ask me these types of people are everywhere. Fortunately for them and unfortunately for everyone else, church is for *everybody* especially those that are poor in spirit.

When I first moved to Texas, to a majority-white city, one of my biggest goals was to find a church. My reasons were simple: I was alone. Although I did meet a coworker who shared a similar church upbringing, just knowing that someone else understood where I was coming from made me feel not so alone. I didn’t know anyone, and I knew that church would be a sort of safe haven for me.

Being Black in America, not just in the South, means that church is in our blood. Despite religion and church being used against them, my ancestors took the religion of their oppressors and used it to inspire hope, optimism, and even Hoodoo. Church reminds me of the resilience our ancestors showed while enduring torture, psychological trauma, and other unspeakable cruelties. It’s easy to dismiss going to church as unnecessary, but one often forgets that the Black American church, regardless of denomination, is the heartbeat of our community. It’s the backbone of us as a people.

Church is not just about religion or worshiping God; it’s about community. It’s about our successes and our failures. It’s disheartening to see that the Black Church, specifically, isn’t as popular as it once was. It begs the question: have we, as a people, forgotten our roots? Have we lost the plot? I have more questions than answers as I write this, but something I know for sure is that the Black church began as a place for building faith and community.

Although its glory days may be behind us, they’re not forgotten. I grew up in the church, and some of my favorite childhood memories took place there. Reflecting on this warms my heart, knowing I had this magical experience. Churches today may be different, with aging and dwindling congregations, but the Black church, like its people, remains a symbol of resilience and courage. More than a building, its significance and memory continue to live on in my heart.

Thanks for reading, suge. I’ll see you next time. And if you’re thinking of skipping out this Sunday, maybe you should think again.