Ebony and Jet magazines: The legacy of Black media

John P. Johnson put his ENTIRE FOOT in these magazines!

Happy Sunday, Brunchers! And Happy March! I hope you’re having a pretty good Sunday so far. If not, I hope you have a better day tomorrow and a better Sunday next week.

When I first decided to write about the legacy of Johnson Publishing Company, it came about randomly. I was scrolling on Twitter and came across a video posted by a fashion blog. Now, I have a confession to make: I am a huge fashion nerd, more from a visual perspective than wearing curated pieces. Of course, if I could buy every staple piece from every runway and fashion house, I would, but that’s just not feasible!

Anyhow, this blog was behind the scenes at a runway show, and an interviewer posed the question (not verbatim), “Who do you think is the most overexposed artist?” Cue unnecessary and weird disparaging remarks about Beyoncé. Understandably, I was annoyed because I am a huge fan of Bey (#Beyhive), BUT what the hell does that have to do with fashion? Nothing! The opportunity to ask what the interviewee was wearing, who their favorite designer is, or which fashion house they think is the most experimental — all of those questions were right there, instead, they chose to ask something with the sole purpose of rage-baiting and driving traffic to their blog.

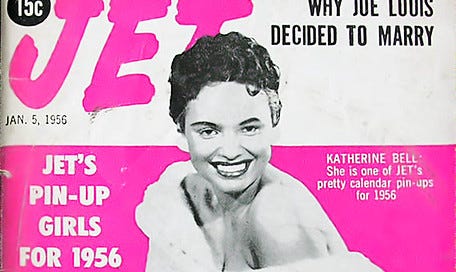

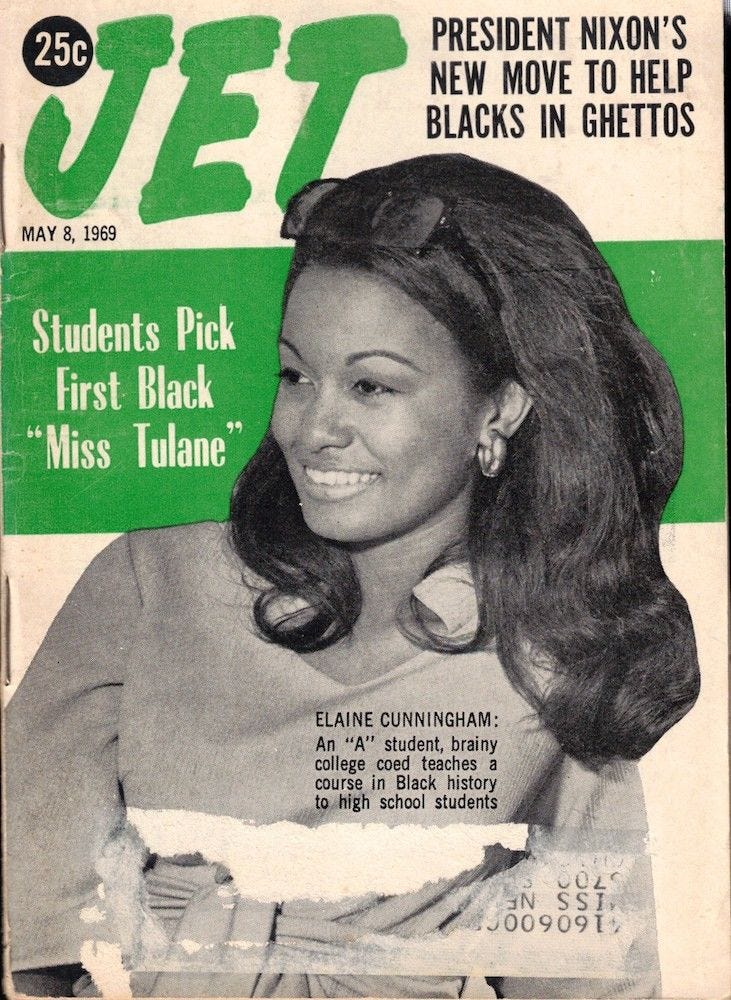

Excuse me? When did we stop taking journalism seriously? I am a writer, soon-to-be-published author, and not a journalist, but anyone with eyes could see the lack of professionalism and decorum here. That video drove me down a rabbit hole of memories — back to when I would read magazines as a child. I have vivid memories of my cousin and me snatching the new Jet magazine off the kitchen table and running to the living room to look at Jet Beauty of the Week. I wasn’t a Seventeen, Cosmo, or Teen magazine reader. I was an Ebony one! Kudos to my grandmother for securing that subscription.

Anyhow, let’s get into the legacy of Ebony and Jet. Aht! Aht! I don’t wanna hear NATHAN about Essence. That ship has sailed, chile. And yes, Jet and Ebony are available online, but they are no longer owned by Johnson Publishing Company.

When John H. Johnson founded Johnson Publishing Company in 1942, he not only created a publishing business but inadvertently broke ground for all things Black American. With just $500 borrowed against his mother's furniture, Johnson launched Negro Digest, which later evolved into the empire that would produce Jet and Ebony magazines. As a son of Arkansas sharecroppers, he understood the power of controlling our narrative. "If you don't tell your story, someone else will tell it for you," he famously said. This philosophy fueled publications that centered on Black experiences, achievements, and challenges during times when mainstream media largely ignored or stereotyped Black Americans.

"If you don't tell your story, someone else will tell it for you," he famously said.

Perhaps nowhere was the impact of Johnson's publications more evident than during the Civil Rights Movement. When 14-year-old Emmett Till was brutally murdered in Money, Mississippi in 1955, it was Jet magazine that made the brave decision to publish the photographs of his mutilated body, images that his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted the world needed to see.

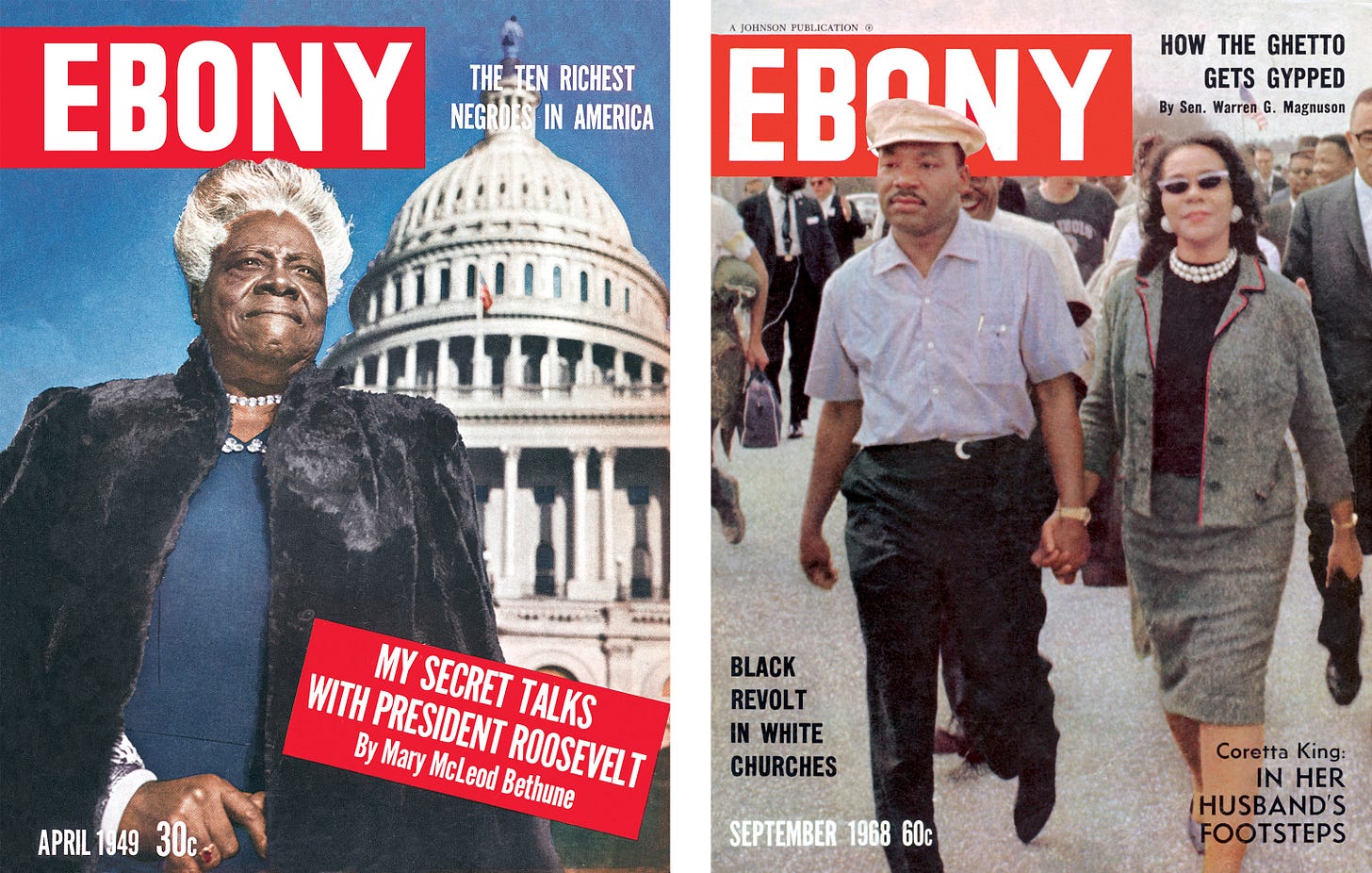

"I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby," she said. And see they did. That September 1955 issue of Jet became a catalyst for the movement, shocking the conscience of America and mobilizing support for civil rights legislation. Throughout the turbulent 1960s, while many mainstream publications reported on civil rights from a distance, Jet and Ebony reporters were on the ground in Black and Southern communities, documenting protests, interviewing movement leaders, and providing nuanced coverage that respected the dignity of those fighting for equality.

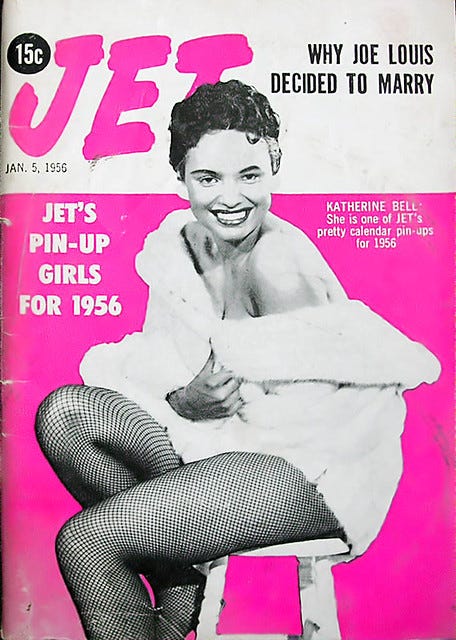

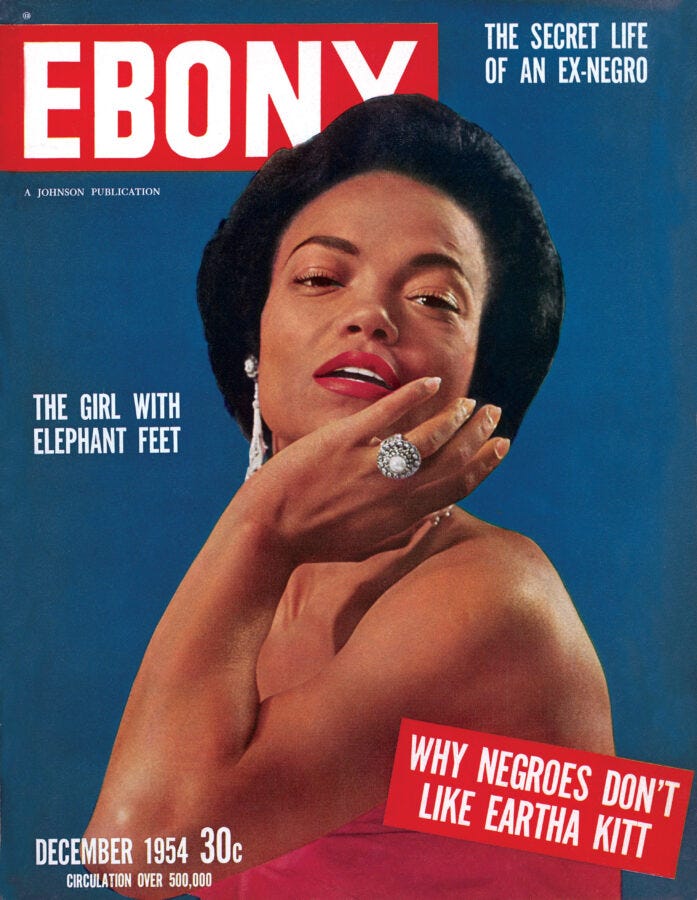

The magazines didn't just report history. They helped shape it. Countless important figures were made the face of a Jet or Ebony cover in these years. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a special relationship with these publications, often using them as platforms to communicate directly with Black America. Many of his speeches and essays found their way into Jet and Ebony's pages, reaching households where his words might otherwise never have been heard. Long before "Black excellence" became a hashtag, Ebony and Jet were showcasing it on every glossy page. These magazines transformed how Black celebrities and public figures were presented to the world, particularly those with Southern roots.

When Hollywood limited Black actors to stereotypical roles, Ebony photographed them in glamorous settings, highlighting their sophistication and humanity. When mainstream fashion magazines excluded Black models, Ebony's Fashion Fair showcased Black beauty in all its diversity. When mainstream media neglected to cover the achievements of Black professionals, entrepreneurs, and intellectuals, Johnson's publications celebrated them as heroes.

For communities like mine, especially, seeing someone from your hometown in Jet or Ebony wasn't just exciting. It was affirming! From Birmingham's Angela Davis to New Orleans' Mahalia Jackson, from Atlanta's Martin Luther King Jr. to Mississippi's Oprah Winfrey (I don’t care for Miss Ma’am, but her achievements are something to take note of), these magazines showed us possibilities and potential that transcended stereotypes about the South.

The annual Most Eligible Bachelors and Most Beautiful Women issues became cultural events. The wedding announcements in Jet were followed as closely as white folks followed royal marriages. And the advertising, featuring Black models using products specifically designed for Black consumers, and sometimes not specifically, but advertised to us regardless; helped establish a market that many previously claimed didn't exist. Becuase of this fact, I almost wrote about Pepsi’s relationship with the Black community, but then I thought back to that Kendall Jenner fiasco, and, nah. ALMOST THOUGH!

So the story of Jet and Ebony cannot be fully told without acknowledging the seismic shifts in media consumption that eventually led to their transformation. The death of print media hit Black publications particularly hard, creating a void that digital platforms have struggled to fill in the same meaningful way. When Jet ceased its print publication in 2014, transitioning to a digital only format, it marked more than just a business decision. It signaled the end of an era. The physical presence of these magazines in our homes, barbershops, beauty salons, and churches was part of their power. They were tangible evidence of our stories being told, our beauty being celebrated, our politics being discussed.

The decline of print media meant more than just changing how we consume information, it disrupted crucial economic ecosystems within Black communities. Johnson Publishing employed Black writers, photographers, editors, graphic designers, and sales representatives at a time when mainstream publications rarely opened their doors to Black talent. These jobs created pathways to the middle class for many families and helped establish Black media professionals who later influenced mainstream publications.

Moreover, the advertising dollars that once flowed to Black print publications have largely been redirected to digital platforms owned by tech giants rather than Black media entrepreneurs. This shift has weakened the economic foundation of independent Black media, making it harder to sustain the kind of in depth reporting and cultural documentation that Jet and Ebony pioneered.

In the transition from print to digital, the ritual of discovery was lost. Unlike algorithmic feeds that serve us more of what we already know, flipping through Jet or Ebony meant encountering stories you didn't know you needed to read, seeing faces you might not have sought out, and developing a broader sense of community beyond your immediate circles.

Though Johnson Publishing Company filed for bankruptcy in 2019, and both Jet and Ebony have changed ownership, their legacy remains indelible. The archives of these publications of over 4 million images documenting more than 70 years of Black American life were saved from auction in 2019 when a consortium of foundations purchased them for $30 million, ensuring this cultural treasure would be preserved.

Today, as we navigate an increasingly fragmented media hellscape, the blueprint these publications created remains relevant. They taught us the importance of owning our narrative, celebrating our culture, and documenting our history with honesty and dignity.

The Black experiences they captured, from rural church gatherings to urban freedom marches, from family reunions to celebrity homecomings, created a visual and written record that connects generations. They show us where we've been and help us imagine where we might go.

Despite the challenges facing Black media today, new digital publications are finding innovative ways to carry forward the Johnson legacy. Platforms like Blavity, and The Root are creating spaces for Black voices while embracing the technological tools of our time. Yet many media observers note that the cultural authority once held by Jet and Ebony and their ability to shape the conversation within Black America remains unmatched in today's fractured media environment.

Do you have any memories of these mags? Drop your stories in the comments below. Rather, it’s about a memorable cover, how these magazines shaped your understanding of Black identity, or how you think we might recapture the magic of Jet and Ebony in today's digital landscape.

Our collective memories keep this legacy alive, so let's remember together the golden days of these publications that didn't just report our history but helped us make it. I’ll see you next time!